Lonicera, or honeysuckle, is native to North America, North Africa, and Eurasia. While there are about 158 species, the two that showed up most often in my research were Lonicera japonica and Lonicera pericyclemenum, so I’m going to focus on those two.

Before we get into this, let’s talk general toxicity. Honeysuckles are wily. Some species are completely toxic, some are only partially toxic (as in, leaves and berries but not flowers), some aren’t toxic at all. SO, if you’re going out foraging, be very careful with these plants. Lonicera japonica is currently only used for its flowers and nectar as far as I could tell, so I wouldn’t attempt to eat any other part of it. Lonicera periclymenum is said to be entirely mildly toxic, but I also found recipes for pudding using its flowers. There is one variety I could find that definitely has edible berries, Lonicerum caerulea. These berries have been studied by scientists and are actually very good for you. It seems the rest of the lot have toxic berries, though. Fortunately, the nectar of all species is safe to eat, so you’ll always be able to suck that honey.

Lonicera japonica, or Japanese honeysuckle is native to East Asia and parts of China, where it has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for over a thousand years. Currently it is farmed for its flowers which are used to make everything from tea and wine, to pills, powders, and even injections. Here’s a deep dive if you’re interested in how it’s harvested, prepared, and used. Primarily it’s used as a cure for upper respiratory infections. This is use is backed up by science, L. japonica has antiseptic, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties, among a host of other good stuff.

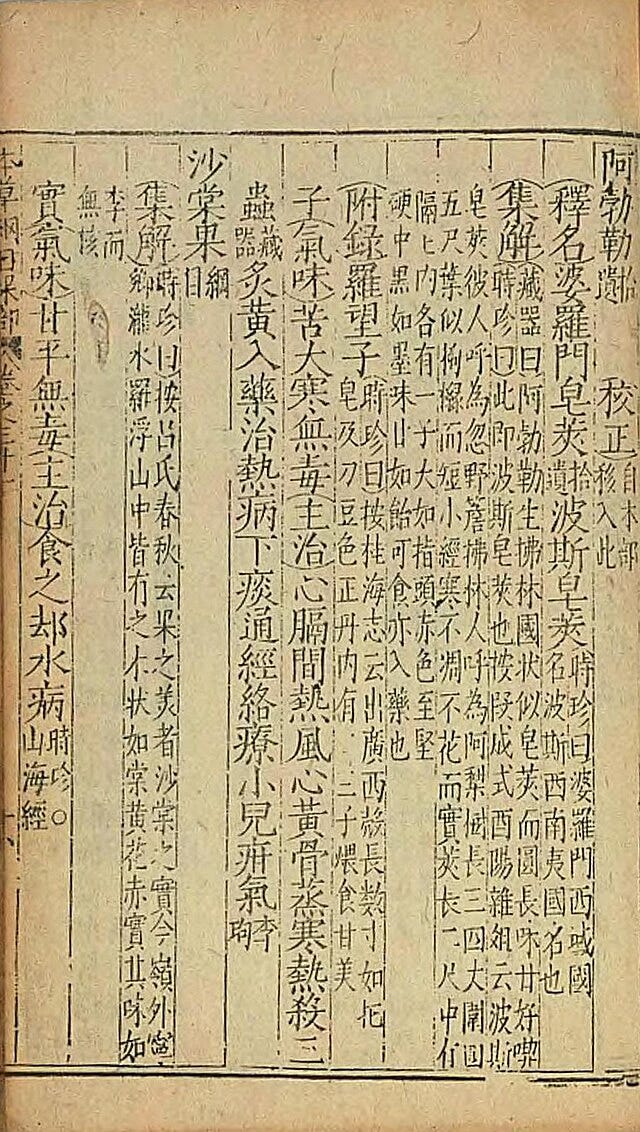

Honeysuckle is also mentioned frequently in the Bencao gangmu (I also saw it written Ben cao gang mu). Written by Li Shizhen and first published in 1596, the multiple volume work includes medical knowledge, herbology, and natural history. Honeysuckle is mentioned in volumes III, IV, and V in recipes along with other plants to help cure everything from achy legs and skin boils or lesions, to several ailments involving qi, particularly illnesses of wind. I’m not going to try and explain wind, qi is very nuanced and I’ll mostly likely mess it up. But, I did find an in-depth explanation here, if you’re interested.

I actually have one of these right outside my front door. I purloined a cutting from a hedge I came across on a walk with my dog Wednesday (RIP sweet girlie) a few years ago. It hasn’t flowered yet, but I’m crossing my fingers for this spring. An important thing to keep in mind if you live in the US is that L. japonica is considered a noxious invasive. I have mine in a container so it can’t spread vegetatively, and I plan to harvest the flowers when it finally blooms, so it can’t spread via seed either.

OK, so let’s get on to L. periclymenum, or European honeysuckle. This one is much more folklore heavy. The lore here is pretty interesting, and much of what I found came from the UK. Planted outside, honeysuckle, also called woodbine, brings luck, protection, money, and increases psychic powers. Bring its flowers inside, though, and you’re apparently asking for bad luck. This might have to do with its supposed ability to grant erotic dreams to young women and of course, in times long gone (cough cough) women’s sexuality was all but taboo. It could be that the erotic dreams of young women were equated somewhere along the way with bad luck, but I couldn’t find anything suggesting that. So who knows… Honeysuckle was also known as both witch-snare and witch-scape because you could either catch a witch in a hoop made of it, or she could use its vines to escape if she was being chased.

According to Richard Folkard Jr.’s Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics (1884), in France honeysuckle was frequently planted in graveyards. He quotes the French journalist and novelist, Alphonse Carr as saying:

There is a perfume more exciting, more religious, even than that of incense; it is that of the Honeysuckles which grow over tombs upon which Grass has sprung up thick and tufted with them, as quickly as forgetfulness has taken possession of the hearts of the survivors.

So goth, I might have to check out some of Carr’s novels… Interestingly, he was an avid floriculturist and was the man who gave the dahlia its name.

L. periclymenum was also known as goat’s leaf because it twines and grows in high places where only goats fear not tread, or because goats like to eat it, possibly a little of both. Also, it’s a well known habitat for dormice, which are such sleepy cuties I can’t even.

So there you have it. Plant it for its delicious nectar, but choose a native! Don’t be like me and thieve an invasive just because it’s pretty and no one is looking.

Hey there! Here’s how plant horror in the coven works:

First week of the month - The Lab (that’s this post!) - Free for everyone.

Second week of the month - The Witch Lab (a short, horror piece from a plant witch’s journal detailing one of her experiences helping (I use the term loosely) a client using the featured plant of the month - New episodes are free! The back catalogue is going to remain paywalled largely because un-paywalling it is time consuming and I am busy doing horrifying things.

Third week of the month - The Grim Grimoire (an entry from The Witch’s spell book detailing how she uses this plant for her dark magic including spells, chants, recipes, instructions, and more). The text version of this will be free, but a digital zine version will go out to paid subscribers. The back catalogue will remain paywalled for the reason stated above.

Fourth week of the month - 100% Plant-Based Horror story featuring the month’s plant. These are longer stories that include everything from ghosts, to parasites, aliens, experimental supplements, monster trucks, extinct species, serial killers, and more! - Paid subscribers only, here’s a freebie you can read to check it out!