Ficus carica is perhaps one of the most well known of the ficus family, as it is the ficus whose figs are most commonly eaten. By way of introduction, this is Figglet, my Ficus carica.

Figglet is a young black mission fig and still hasn’t put out any fruit, but believe me, I am anxiously awaiting that day. Ficus are pollinated by very tiny wasps known as fig wasps. The entire cycle is bonkers, but we won’t get into right now for two reasons, one, I have that discussion planned for another post, and two, Ficus carica used in fruit production are parthenocarpic, meaning they can produce viable fruit without pollination. So no fig wasps in your, well those figs anyway.

But we’re not out of the reproductive woods yet, because Ficus carica is a great example of how nature (when we actually pay attention to it) turns our perceived notion of gender on its head. For those of us who don’t mind rethinking and restructuring our beliefs when we get new, more accurate information about our world, this revelation isn’t going to come as much of a shock; nature is much more varied than male and female. Ficus carica is a great example of this complexity. The technical term for what we’re about to discuss is gynodioecious, which just means that a species can have only female flowers on some plants, and bisexual flowers and female flowers on another. But it’s not an entirely accurate description plants like Figglet.

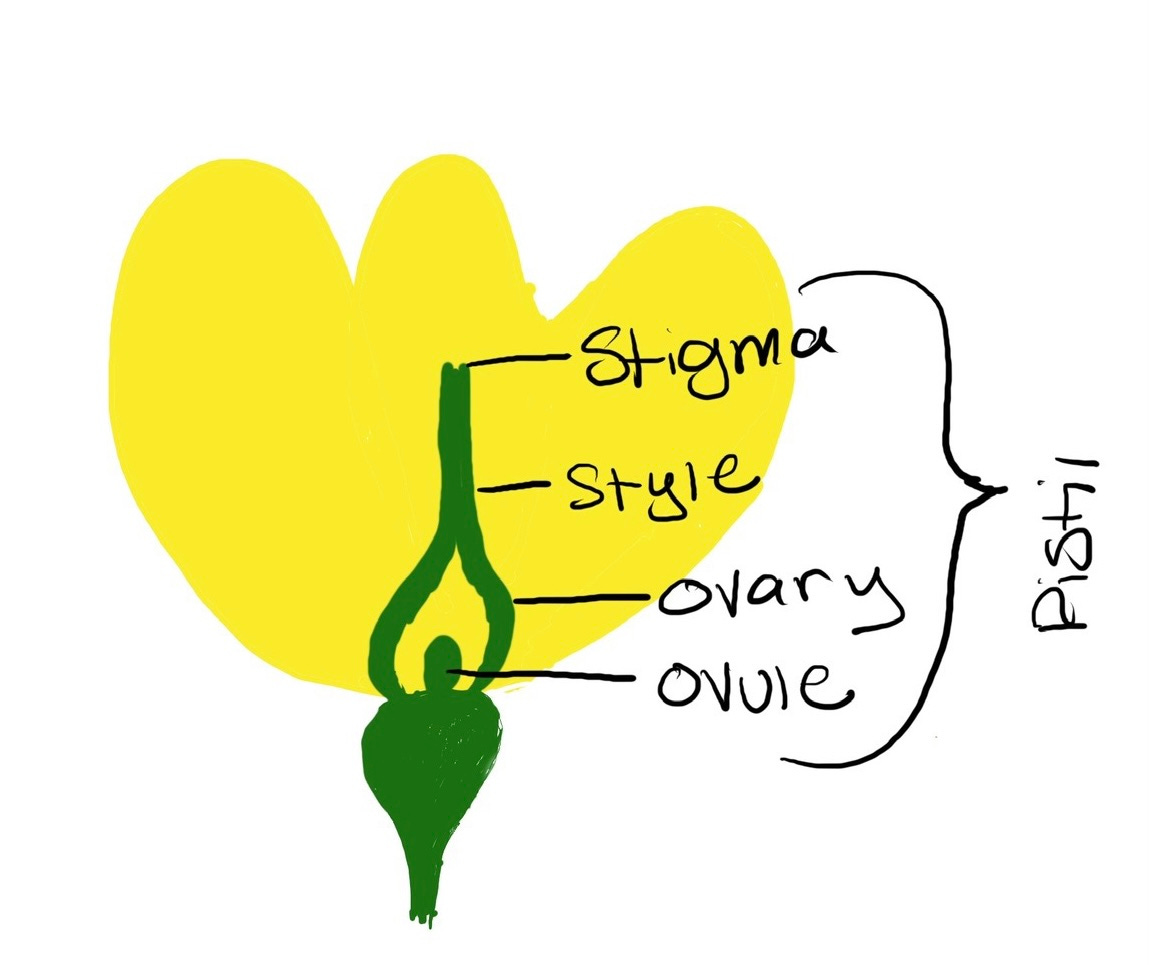

So here we go. Below is a flower with only female parts. The stigma is sticky and generally kind of cup shaped so that pollen will stick to it and then fall down the hollow style into the ovary.

In a male flower, as in the male cucurbit flower below, you generally get one large stamen covered with pollen.

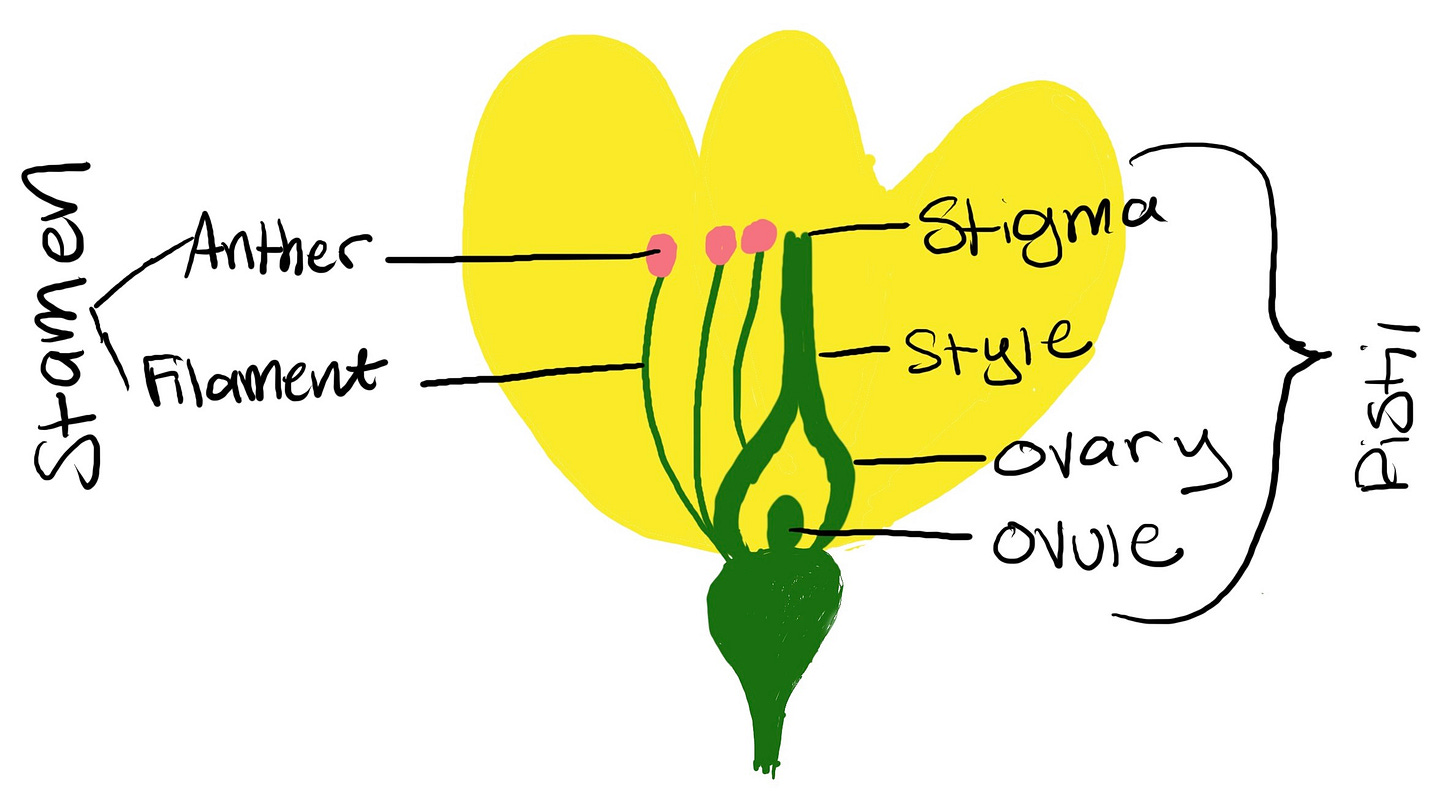

Most flowers are bisexual, meaning they have male and female parts all in the same flower.

In this hibiscus from my balcony garden you can see the yellow, pollen bearing stamens and the red stigma of the pistil.

So as we’ve discussed before, ficus don’t have typical flowers, they have a syconium, which is a hollow structure with flowers on the inside. All of the tiny filaments you see on the inside of the fig below are the hundreds of flowers and fruit inside the syconium.

In Gynodioecious plants, like Ficus carica, some trees have all female flowers, other trees have bisexual flowers and female flowers. Because these trees produce pollen in their bisexual flowers, they’re called male trees, even though they don’t have any male flowers, seriously, there has to be a better name, right? Here’s where it starts to get even more complicated. One type of fig, the caprifig, Ficus carica sylvestris, has only male flowers and produces inedible fruit. The pollen from these figs is often spread by fig wasps to the edible Smyrna variety of Ficus carica, which has female flowers and/or bisexual flowers (the type of flowers I think depends on the variety of tree, if I’m understanding the internet correctly). Anywho, plant gender is not as simple as male and female, plants clearly do not care for dichotomies.

But there’s more to Ficus carica than a deeper understanding of the diversity of plant gender. According to the American Botanical Council:

The earliest evidence of human consumption of figs comes from Pre-Pottery Neolithic A sites (ca. 10,000–8,800 BCE) from the Jordan Valley to the Upper Euphrates (mountains of southeastern Turkey).

That is a long time ago, my friends. And it’s no wonder that figs have been cultivated for so long, they’re good for your blood pressure, can help lower blood sugar, are high in fiber, low in fat, anti-inflammatory, and really, really tasty. They can be dried for storage and can be used in savory dishes or desserts. And their long history means they have a special place in mythology as well.

Roman natural historian Pliny linked the fig tree to the ancient Roman goddess Rumina, the goddess of breastfeeding mothers and infants, both human and animal. Rumina is classified as one of the indigitamenta, archaic deities who didn’t have the complex personalities of the later Roman pantheon. A fig tree at the base of the Palatine hill, near Rumina’s shrine was known as the ficus Ruminalis, or Rumina’s fig. The milky white sap of the ficus could have strengthened the association with this goddess. The ficus Ruminalis is also associated with Romulus and Remus, whom legend says were suckled by a she-wolf in a cave near the spot where it used to stand.

According to the University of Chicago the ficus Ruminalis began to die in 58 CE, priests at the shrine believed this was a bad omen, but after the tree died back to the ground, new shoots sprang from the roots, extending its life.

Now you’ve read the research, upgrade to a paid subscription to see what aspect of the Ficus carica I turn into a 100% plant-based horror story on September 1st.

So dioecious is as opposed to monoecius; two houses (meaning plants have either male or female flowers) versus one house (male and female flowers on the same plant). Monoecious plants can have either perfect (male and femal parts in the same flower) or imperfect (only one functional sex organ in the flower) flowers. Gynodieocious simply refers to a plant that is either monoecious with perfect flowers or can be unisex with only female flowers (i.e. it is never truly dioecious).

Boy that's a lot of botany to remember!

Plants are different than animals in that they exhibit alternation of gnenerations (they alternate between haploid forms and diploid forms) but they still exhibit only two sexes; that is ovum producing female parts and spermatozoa producing male parts. It just get confusing in how those parts can be arranged, hence the mutliplicity of terms to describe plant reproduction.

I must do that!